With minor league baseball ever evolving, Padres aren’t afraid to push boundaries

Jackson Merrill the latest example of Padres relying on the player — and not the minor league level — to determine when he’s ready for the big leagues

First, Jackson Merrill was a shortstop deep in the shadow of a generational talent. He was blocked at every position on the infield. As he made his way to big-league camp in February, he did so with fewer than 50 games above A-ball.

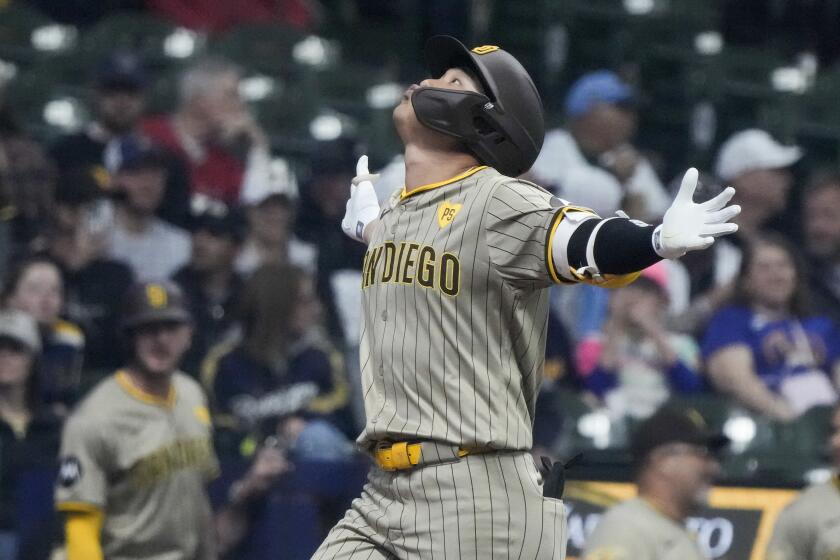

Merrill never dwelled on any of this on his way to this week becoming just the third center fielder since 1965 to start on opening day before his 21st birthday.

The Padres certainly did not dwell on an unconventional path up the system, either. They never have under general manager A.J. Preller.

“We lean toward being more aggressive with players,” Padres assistant farm director Mike Daly said. “ … It’s a number of factors. Yeah, these guys are talented. But these guys have a slow kind of clock. They’re able to see the game and make really good decisions, are really good people. They’re very hard workers. And that just gives us a comfort level organizationally to be able to put stuff on their plate and to challenge them.”

Fernando Tatis Jr. remains the bright, shiny example of what the fruit of such aggressiveness can look like — though at least he had more than 400 plate appearances above A-ball when he made the jump from Double-A San Antonio to the majors in 2019.

The history of prospecting, of course, is littered with cautionary tales of can’t-miss players who even took traditional paths to the majors, experienced failure and were never the same.

The Angels’ Brandon Wood, for instance, was Baseball America’s No. 3 prospect after hitting 43 homers in 2005 in the California League. He stopped at each level before making his MLB debut two years later and had a .513 OPS in the majors when he flamed out of the game entirely in 2014.

Among the Padres’ recent examples, Matt Antonelli was No. 50 in Baseball America’s top-100 after posting an .894 OPS after moving from A-ball to San Antonio in 2007. He struggled mightily the following year at Triple-A Portland (.657 OPS), was still a September call-up in 2008 (.573 OPS) and never again played in the majors.

Likewise, Jo Adell and Jarred Kelenic are still trying to find footing in the majors after ranking among the top five prospects in the game at some point.

You can do everything by the book and still miss.

“Development isn’t linear,” Daly said.

Especially not of late.

The pandemic wiped away the 2020 minor league season, leading the Padres to judge whether their top prospects were progressing enough to help a postseason push at an off-site “COVID camp.” Catcher Luis Campusano and pitcher Ryan Weathers were called up to the majors without playing an inning above A-ball that year. Both have had up-and-down journeys since, with Campusano finally the unquestioned starter behind the plate this season and Weathers starting anew with the Marlins and competing for a rotation job.

The ensuing contraction of more than three dozen minor league teams cut an entire level (short-season) out of the climb to the majors. The restructuring capped the number of players a team could roster both domestically and at international academies — 165 this year in the United States and 70 abroad once the Dominican Summer League starts — and that only increases the rate of the roster churning that occurs when draft classes join systems each summer.

It’s all added up in recent years to teams figuring out on the fly what promotions will look like moving forward, and the Padres have not been shy about testing those boundaries.

“We can evaluate over time whether that’s good or not as good,” said Padres manager Mike Shildt, whose background is steeped in player development. “But it is, again, normalized throughout the industry. Everybody’s got their own philosophy individually, organizationally, how they do that, but the process of accelerating players to get to the big-league level is greater than it’s been in the history of the game.”

The amateur showcase circuit, the amount of social media attention on those players and readily available access to professional-level preparation, Shildt said, has prospects better prepared than ever as they step into minor-league systems.

In San Diego in particular, an emphasis is placed on learning who these players are before amateur scouting director Chris Kemp calls their name in the draft or signs them as an international amateur. While talent is at the crux of the discussion, what the team learns before players even become Padres has often been the basis of aggressive promotions that have raised eyebrows throughout the industry.

Catcher Ethan Salas, just 16 years old, was fast-tracked past rookie ball to low Single-A Lake Elsinore for his professional debut. He finished 2023 at Double-A San Antonio. It remains to be seen where 17-year-old Leodalis De Vries will start his career this year, but the Padres moved him from the Dominican Republic to Peoria, Ariz., to participate in the Spring Breakout prospect game that has been rescheduled for Saturday against the Mariners at Peoria Stadium.

It wasn’t long ago that the Padres hesitated to start their international signees’ pro careers in the United States.

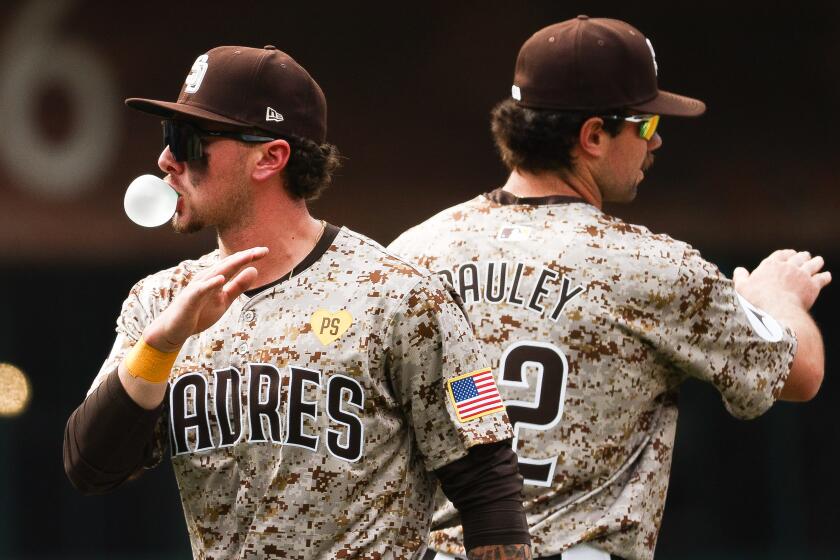

Now their big-league center fielder can’t have a legal celebratory beer until the middle of next month, Graham Pauley joined Merrill on the opening day roster with even less time in Double-A (but a heck of a lot more at-bats in the college) and the catcher of the future might be pushing for a locker at Petco Park as a teenager.

“Each player is different,” Daly said. “We feel that we make the best decisions in the interests of the players with a lot of people’s input, whether coaches and staff and scouts and analytics. … Again, development isn’t linear. So we feel really good about the decisions that we’ve made. But we’re always looking at that to kind of see and think what is in the best interest of the player.”

The biggest data point in all of this: What the player tells the team.

Merrill’s bat, for instance, told the team he was a high-end prospect when the industry considered him a pop-up prospect out of the Baltimore region (one team official continues to scoff at the term; that means the Padres’ scouts did their homework on a player and the industry did not). Their reports and analytics see a swing that will play in the majors when injuries have robbed Merrill of minor league seasoning.

What they know of his makeup tells the Padres that Merrill can handle failure when it inevitably knocks him down a peg (or four) as it does everyone at some point.

Then there’s actually what Merrill has told the Padres, so to speak, throughout this grand experiment to see if he could indeed jump from a Double-A shortstop to a major league center fielder in one spring.

“I’m not saying I was expecting to be the center fielder on opening day, but I was putting myself in position to be somewhere on the field at least,” Merrill said this week in Seoul, South Korea. “I didn’t really care where it was. I’ve been saying that since the day I got drafted — (that) I don’t really care. Even when Fernando was a shortstop and everybody asked me, ‘What are you going to do if you can’t play short?’

“I was like, ‘I don’t care where I play. I just want to be on the field. I just want to be part of the team.’”

Go deeper inside the Padres

Get our free Padres Daily newsletter, free to your inbox every day of the season.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.